Together with a couple of other pilgrims, during the holidays in May, we set out to the third „finger“ of the Chalkidiki peninsula in Greece, where in the small town of Ouranoupolis our host was waiting for us. Our ultimate objective was the Bulgarian monastery St. Georgi Zograph in the monastic republic of Mount Athos. In the year 963 monk Athanasius founded the Great Lavra, the biggest of the 20 monasteries in existence. In our day any man professing Christian Orthodoxy should visit it at least once in his lifetime (women are not allowed here). The only way to reach the monasteries is by sea. We decided not to go by boat but took the ferry which covers the distance in over an hour but has an open terrace with a stunning view. The deck was packed with pilgrims – from Bulgaria, Greece, Russia, Serbia, Moldova, Romania...

Unlike the pilgrims of other nationalities, when they visit Athos Bulgarians are rarely accompanied by a spiritual advisor. However, an intelligent and convivial Bulgarian priest takes the seat next to us, on his way back from a trip to the Russian Patriarchate. He readily talks about Mount Athos and the role of the Bulgarian monastery there, a monastery that once even helped Alexander Stamboliiski‘s government pay the heavy reparations after World War I with all the gold it had. From him we find out that the St. Zograph is undergoing an olverhaul – of the 8-storey building known as the „bath wing“ which burnt in a fire – and also that the monks there grow their own olives and make their own bread, olive oil, brandy and wine. We also learn how the monastery got its name. According to legend, the monastery was founded by three brothers – Moses, Aaron and Ivan Selima from Ohrid in the year 919. The earliest document testifying to its existence is dated to 980. But the monks didn‘t know which saint to choose as its patron. So, they took a piece of wood to portray their patron on and after leaving it in the church took to earnest prayer, entreating the Lord to reveal to them the name of the saint. The next morning, to their surprise, they saw that St. George had been depicted on the piece of wood and they called him Izograph – self-drawn.

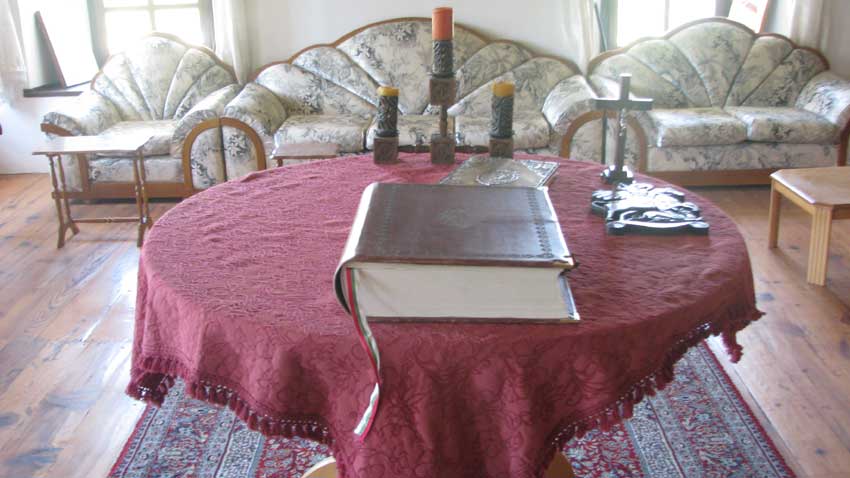

At the pier of the Bulgarian monastery we help a returning monk with his luggage and he returns the favour, inviting us inside the waiting car. So, instead of an hour‘s climb up the mountain, we find ourselves inside the cloister in just ten minutes. And luck strikes again – there we are welcomed by the abbot himself. There‘s hustle and bustle all around because preparations are in full swing for the monastery patron saint day on Gergiovden, St. George‘s day, but also because of the pilgrims coming from Bulgaria and the men living in the monastery who are engaged in the renovation or are helping in the monastic kitchen. At one end of the yard cauldrons of water are steaming and we find out, to our surprise, that two smiling monks are decorating an extra 1,000 eggs (all of them painted red) for the guests expected on St. George‘s day. Inside the clean refectory the food is served right after each church service. The food is simple – fish soup, boiled chickpeas, a piece of cheese and monastic bread – fish is only served on feast days and we were there on the eve of St. George‘s day. Monks pass around the table and offer a glass of monastery wine.

The changes at St. Zograph are there to be seen: a new wing has been built, housing quarters for the pilgrims. A huge tower crane is rising above the „bath wing“ as if in confirmation of the fact that the renovation continues and that very soon this part of the monastery will regain its splendour. The space around the monastery building is also impressive: magnificent supporting walls are being put up, on them master craftsmen from Serbia are making enormous mosaic icons.

One thing is certain: St. Georgi Zograph is a haven of the Bulgarian spirit. We are amazed to see that the doors to the sleeping quarters and all personal belongings remain unlocked and that at night, very expensive smartphones are left to be charged out in the corridors – for fear of fire the corridors are the only place with power sockets. At around 4 AM we sneak out of our room to find ourselves bewitched by the monastic chants that will continue until 8 AM in the monastery‘s main church. But before we step inside it – for a moment or for eternity – we freeze under the star-studded sky over St. Zograph. We do not wait for the shared breakfast in the refectory and surrounded by the morning scent of the roadside jasmine go down to the monastery port on foot. Here too the renovation is evident and next to the watchtower, the run-down wind mill awaits its turn to be repaired. We take the ferry and head back to the civilization of Ouranoupolis. The hustle and bustle of the resort town, the vain glory overtake us but we know the memory of these almost 24 hours we spent in a different realm, a realm of humility, far from the pettiness of the world, will stay with us for a long time.

English version: Milena Daynova

Photos: Yoan KolevThe newest exhibition at the National Museum of Military History in Sofia, 'War and the Creatives: A Journey Through Darkness' opens today, offering free entry as a gesture to those who were unable to visit during the recent renovations. Rather than..

A 5,000-year-long history lies hidden in the ruins of the medieval fortress “Ryahovets” near the town of Gorna Oryahovitsa where active excavations began ten years ago. On this occasion, on November 17, the Historical Museum in Gorna Oryahovitsa..

Just days ago, archaeologists uncovered part of the complex underground infrastructure that once served the Roman baths of Ratiaria - one of the most important ancient cities in Bulgaria’s northwest. Founded in the 1st century in the area of..

+359 2 9336 661