The parents

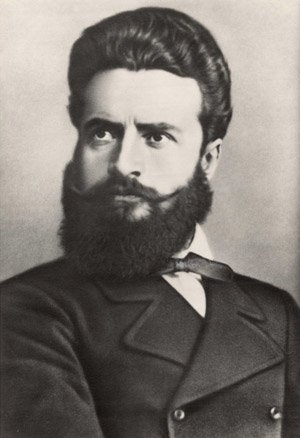

Where did this genius come from? Part of the story is about genes. Hristo was the son of а renowned teacher, Botio Petkov. Furthermore, his intense poetry took generous handfuls from the beautiful Bulgarian folklore. But unlike his fellow-poets, Hristo Botev transformed the beauty of folklore into an unmistakable amalgam of bold ideas and emotions. Amazingly, without any viable background and of any great predecessors or rivals on a rather amateur literary scene and with 26 poems published all in all, Hristo Botev is indisputably Bulgaria’s greatest poet of all time. How sad – the first great modern poetic talent of Bulgaria is her greatest one.

But even more amazingly, Hristo Botev never thought poetry was priority. It was just one of the frills in his “career” of a rebel fighting for the liberation of his “enslaved” fatherland. His family wanted to give him sound education and sent him to Russia, but the young rebel was expelled from school. Botev then went into permanent exile in Romania where he teamed up with the rebellious part of the Bulgarian community there who organized a powerful revolutionary committee. Hristo Botev lived in utter poverty, got married – allegedly for money; was sent briefly to jail for theft that he committed for the cause of liberation, etc. On the surface he was a rascal, a failure! However, that man emanated an incredible charisma and brilliance. He published a few newspapers for which he wrote wonderful samples of journalism. And his poetry was absolutely stunning. Here is one of his works, My Prayer. In it a man of genius reveals his “private” God.

God of mine, O rightful God,

No, not thou which art in heaven

Thou who art within me, God,

In my heart and in my being.

Not thou, to whom the Orthodox

Candle-burning rabble flocks,

Nor thou, to whom the monks and priests

Make obeisance at feasts.

No, not thou, who once did fashion

Man and woman out of clay,

And thereafter did abandon

Man on earth in slavery.

Not thou, who anoints the Tsar,

The patriarch and cassocked priest

But will not smash a prison bar

To set my ragged brother free.

No, not thou, who teaches slaves

To suffer hell on earth and pray,

Who feeds them even to their graves

With fairy tales of Judgment Day.

Not thou, God of lying tongues

And of shameless tyranny,

Not thou, idol of the dunce

And hater of humanity.

But thou, God of majestic reason,

Staunch defender of the slaves,

Who soon shall witness every nation

Greet with joy your holy days.

O God, in everyone inspire

An urgent love of liberty,

To give the utmost to the fight

Against the people’s enemies.

Strengthen too my resolution,

That beside the rebel slave

Fighting for the revolution

I may also find my grave

Do not leave a rebel heart

To grow cold in foreign land!

Do not let my voice depart

Softly, as in desert sand!

1873

(Translation by Peter Tempest)

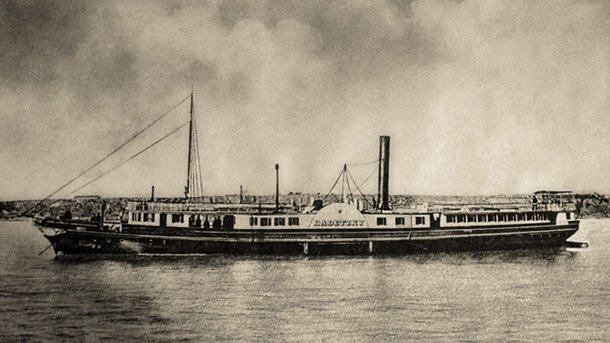

Hristo Botev knew for certain that his prayer would be answered. He was in a hurry to die, and some analysts have said he was suicidal. His golden chance to die a martyr death for his fatherland came in 1876 when he was 28. In the Bulgarian lands, the April Uprising against the Turks had failed, followed by widespread atrocities. The rebellious Bulgarian émigré community in Romania was keen to back the uprising – somewhat belatedly, though. So, Hristo Botev summoned a detachment of about 200 rebels, and prepared to cross the River Danube to join fighting in Bulgaria. To make things absolutely spectacular, he hijacked an Austrian steamship, Radetski. The captain was impressed with Botev's civility, energy and temperament, and agreed to transport the detachment to Kozloduy. Upon arriving in Bulgaria, the rebels kneeled and kissed the earth, saying goodbye to the captain and the passengers.

The Austrian steamship, Radetski

What followed was a downright disaster. There was no one to support in Bulgaria where the uprising had been crushed with unheard of cruelty. The Botev detachment engaged in fighting with Turkish troops, but everything seemed pointless. Many insurgents died in combat. On 2 June, a bullet took the life of Hristo Botev and the detachment dispersed. How did Botev die? In the official version he was killed by a Turkish bullet straight into the heart. However, some historians and writers venture into bolder hypotheses. Some claim that the rebels themselves conspired against him and shot him, once they became aware that their effort was useless. Others say that it could be that Hristo Botev killed himself in an act of total despair. The tragedy was so great that many European media wrote extensively about it. A fine poet and a great Bulgarian patriot and many of his fellows had not died in vain. Following the April Uprising drama and Botev’s exploit, the public opinion across the continent became aware of the plight of a proud Christian nation in the Balkans. In April 1877 the Russian Emperor Alexander II declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The war ended in 1878 and resulted in the restoration of Bulgarian statehood. Hristo Botev’s dream came true posthumously. Well, unfortunately, he had died too young to see the liberation and maybe to give us other pearls of poetry.

Bulgaria’s first modern poet is so far her greatest. The great trendsetter in modern poetry launched one of its darkest trends that went unwaveringly on until mid-20 c. Not unlike their unsurpassed predecessor, quite a few of Bulgaria’s finest poets died violent deaths at a young age. Some committed suicide, others died for their political views. In great Bulgarian poetry death is young.