From the modern Bulgarian translation of the Bible to the threshold of the Nobel Prize

In Bulgarian literature and culture the most famous father and son are indeed Petko and Pencho Slaveykov. They both had talent and mission, and the story of ¬this outstanding family is quite telling of how Bulgarian poetry and its cultural scene changed so fast in the span of a single generation.

Petko Slaveykov (1827-1895) came from a very modest background, his father was a coppersmith, but Petko had a wealth of talented genes, and he easily changed his surname into Slaveykov (derivative from nightingale). This youthful self-confidence was not for nothing, because this energetic guy soon emerged as one of the most outstanding Bulgarian brainworkers of the National Revival. Petko Slaveykov lived in various, mostly Eastern Bulgarian towns, and for a while also moved to Constantinople. He worked as teacher and educationist, journalist, poet, folklorist, translator, and after the Liberation of Bulgaria in 1878, emerged as one of the key politicians in the Liberal Party. He fathered eight children, including the first great ideologist of the Europeanization of Bulgarian literature and culture, Pencho Slaveykov.

Petko’s focus during the National Revival was folklore, poetry and work with the language. He tirelessly collected folk songs and proverbs and published two volumes with folk songs plus a celebrated collection of 17,000 proverbs and sayings. In 1884 he was elected Honorary Member of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

The old Slaveykov was a gifted poet and the wreath of his creative input was the emblematic poem The Spring of the White-Legged bringing the dramatic story of a beautiful Bulgarian girl – the embodiment of Bulgarian collective values – and a Turkish dignitary who wanted to take her to Istanbul, but she refused. In this lovely piece of poetry he portrayed the clash of two cultures – the traditional Bulgarian culture and the Oriental one.

In 1864, while in Constantinople, Petko Slaveykov was invited to join a team for an overall editorial work of the Bible’s translatio into modern Bulgarian. The project was run by two American missionaries, Dr. Elias Riggs and Albert Long. The so-called Constantinople Translation of the Holy Bible was released in 1871. Here is how, some years later, Petko’s son Pencho appreciated his father’s involvement in this enterprise:

“The translation of the Bible spelled the end of the language muddle, to the squabbling of various dialects seeking supremacy in the emerging literary language. Once the Bible was released, the brawls between various dialects of Bulgarian subsided, and the Eastern Bulgarian dialect finally became the common language of all brainworkers and of the nation.”

***

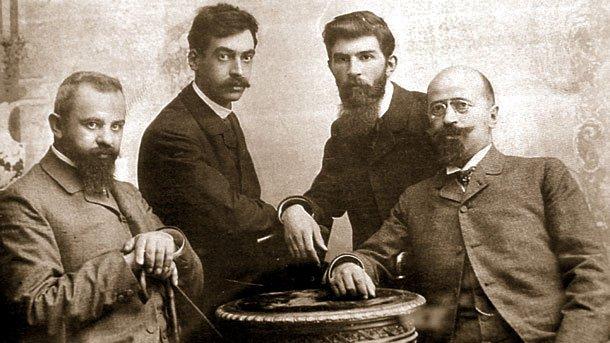

Now crossing into the territory of the father-son relationship, we should caution that the father Petko was often very critical of young Pencho (born in 1866), and even wrote a poem ironizing the teenager’s idleness and naughtiness. This seemingly funny piece could have worked like some sort of a horrible paternal curse, because at age 19, Pencho Slaveykov fell asleep on the winter ice and this left him partly paralyzed: until the end of his life he had to use a cane and had difficulties speaking properly. However, this horrible, debilitating incident worked to give more depth to young Pencho Slaveykov and he accepted suffering as a kind of creative laboratory. On top of that he received high class university training in the humanities – in Leipzig, Germany. A passionate admirer of Friedrich Nietzsche, Pencho Slaveykov took a course for the Europeanization of Bulgarian literature seen as a departure from simplistic images and patriotic themes, and into a major study of the self in its psychological wealth and contradictions. Together with another German graduate, D-r Krastyo Krastev, Pencho Slaveykov was part of the renowned Mysal (Concept ) Circle around the literary journal of the same name. It soon discovered one of Bulgaria’s finest poets, Peyo Yavorov. In the meantime, Pencho Slaveykov himself mastered his poetic skills to outstanding excellence.

In his strongly conceptual legacy, he created works of poetry in which the course of Europeanization of the Bulgarian literature was seen as a two-way process: using and interpreting the ideas of the leading European literary trends on the one hand, and importantly, preserving the national character of Bulgarian literature. The poet borrowed themes from folklore – not unlike his father – but adding novel messages to the simple folklore matter like for example about the divine vocation of the creative person, the power of individual will, and loyalty to the self. Slaveykov provided a broad and philosophical interpretation of beauty: as a regulator of morality. In one of his masterpieces Gory Song, a long poem, he portrayed the chosen personality able to uphold his values in critical moments of national history, and revealed the clash between the exceptional individual and the crowd. In a Nietzschean perspective, Pencho Slaveykov’s entire body of work was focused on Man as the Creator of Being.

In this amazing way, following into the steps of his poet-father, the son transformed his father’s eulogy of folklore-inspired collective values into a eulogy of the gifted, strong-willed individual.

Look at how Petko Slaveykov, the father, saw his mission in his poem A Man of the People

Ever a champion of good causes,

I thought all else a mortal sin.

For public good my own ignoring

I led a life of discipline.

For others I made great exertions –

It was, I said, “the proper line” –

My personal affairs deferring

To deal with their ahead of mine.

The public interest I heeded

Throughout my life – it’s been no joke…

A manifest “,an of the people”,

I’m starving now, barefoot and broke.

And here is how his son Pencho Slaveykov created sophisticated “landscape” poetry that in fact captured the subtle aspects of the psychological state of the self in There is Not a Breeze or Breath in Motion:

There’s not a breeze or breath in motion,

In field and treetop nothing stirs.

The dew has spread a jewel ocean

Where heaven her fair face observes.

Up early on the road I relish

The freshness of a summer dawn

And with invigorated spirits

To journey’s end I’m lightly borne.

To journey’s end, a quiet evening,

Of cloudless skies and the caress

Of restful hearth and home to weave me

A thousand dreams of happiness.

***

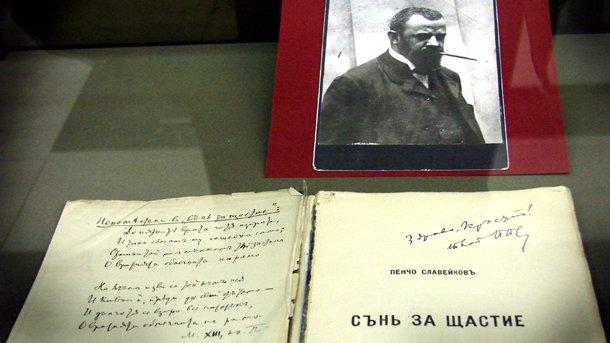

Pencho Slaveykov’s brilliance as both ideologist and practitioner in the Europeanization of Bulgarian culture did not go unnoticed internationally. The translator into Swedish of his Gory Song, Alfred Jensen, planned to propose him for the Nobel Prize in Literature nominations. Unfortunately, the Bulgarian poet died in Italy, in 1912, and the nomination could not reach the Nobel Prize Committee. Today, the emblematic square downtown Sofia with the biggest book market in this country is lovingly called Slaveykov Square. On one edge of the square stands a lovely non-monumental monument of father and son, sitting on a bench in perfect harmony.

English version: Daniela Konstantinova

Verse translated by Peter Tempest