The other day my son, 12, had some problems with a poem he had to learn by heart. I interrupted his efforts, and read to him a completely different piece, Faith by Nikola Vaptsarov. “Hey”, he said, “I like this poet, and you know why, he writes like a rapper!”

How could this poet be so fresh, appealing and no-nonsense for even the internet-ridden generation?

* * *

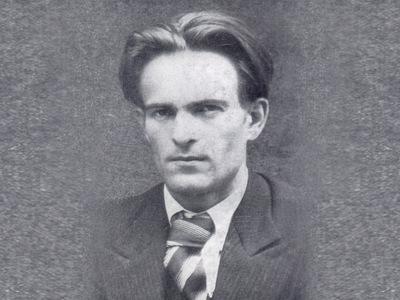

А father whose son died in infancy, а champion of social justice and an antifascist conspirator, an innovative poet sentenced to death and killed by a firing squad at age 32. This is how the life of Nikola Vaptsarov went: ruthlessly, but at least not from the very start.

Nikola Vaptsarov was born in 1909. His home was the mountain town of Bansko, today in Bulgaria but back at that time still part of the Ottoman Empire. His father was a Bulgarian patriot and a Voivode leader from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, a clandestine rebel group that fought for the integration of the Bulgarian ethnic lands in the region of Macedonia with the Kingdom of Bulgaria. The family had good connections in the Royal Palace in Sofia and received Tsar Ferdinand, Tsar Boris III, poets Peyo Yavorov and Elisaveta Bagryana, artist Konstantin Shturkelov and other celebrities. The poet’s mother Elena was a teacher with a good knowledge of English, a rarity at that time, and a protestant. Recalling the childhood of her son she once told the Bulgarian National Radio that as a child, Nikola loved most of all to listen to the tale of Hamlet. When he grew up she wrote down a spiritual testament to her son. In 1959, Elena Vaptsarova gave an interview to the Radio and revisited this testament:

Nikola Vaptsarov was born in 1909. His home was the mountain town of Bansko, today in Bulgaria but back at that time still part of the Ottoman Empire. His father was a Bulgarian patriot and a Voivode leader from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, a clandestine rebel group that fought for the integration of the Bulgarian ethnic lands in the region of Macedonia with the Kingdom of Bulgaria. The family had good connections in the Royal Palace in Sofia and received Tsar Ferdinand, Tsar Boris III, poets Peyo Yavorov and Elisaveta Bagryana, artist Konstantin Shturkelov and other celebrities. The poet’s mother Elena was a teacher with a good knowledge of English, a rarity at that time, and a protestant. Recalling the childhood of her son she once told the Bulgarian National Radio that as a child, Nikola loved most of all to listen to the tale of Hamlet. When he grew up she wrote down a spiritual testament to her son. In 1959, Elena Vaptsarova gave an interview to the Radio and revisited this testament:

“I wrote the following message to him: be strong and courageous, and never let any vanity of this world undermine the basis of your character. Behave with courage at the face of all hardships. And he did follow this testament, like a holy covenant.”

In 1932 Nikola Vaptsarov graduated the Naval Machine School in the Black Sea port of Varna later named after him. As a young sailor, on board the Burgas Ship he had the chance to travel widely, visiting Istanbul, Famagusta, Alexandria, Beirut, Port Said and Haifa. Upon graduation, Vaptsarov took a job as a stoker and later as a mechanic at a foundry in Southwestern Bulgaria.

The one and only verse volume

In 1936 Nikola Vaptsarov was fired from the foundry.It was high time he turned to poetry and to his political ideals. In 1940 he published his celebrated volume Engine Songs. Its front cover illustration features two industrial chimneys belching black smoke. In this unusually outspoken poetry, the working class is desperately suffocated by its hapless industrial existence leaving the poet absolutely indignant on virtually every page.

Bulgaria’s foremost literary scholar Prof. Nikola Georgiev rightfully contends that for Vaptsarov writing poetry was like being – just like breathing, toiling and living. And this has been made beautifully obvious in one of the poet’s best known pieces, Faith:

Here I am – breathing, / Working, / Living

And writing my poetry / (My best to it giving). / Life and I glower

Across at each other, / And with it I struggle / With all my power.

Life and I quarrel, / But don’t draw the moral / That I despise it.

No, just the opposite! / Though I should perish / Life with its brutal

Claws of steel / Still would I cherish, / Still would I cherish!

For Life there is nothing / I would not dare, / I would fly

A prototype plane in the sky / I’d climb in a roaring / Rocket, exploring

Alone / In space / Distant

Planets / Still I would feel / A joyous thrill

Gazing / Up At the blue sky. / Still I would feel

A joyous thrill / To be alive / To go on living.

But look suppose, / You took – how much? – / A single grain

From this my faith. / Then would I rage, / I would rage from pain

Like a panther / Pierced to the heart. / For what of me

Would there remain? / After the theft / I’d be distraught.

To put it plainly / And more directly – / After the theft

I would be naught. / Maybe you wish / You could erase

My faith / In happy days, / My faith

That tomorrow / Life will be finer, / Life will be wiser?

Pray, how will you smash it? / With bullets? / No! That is useless!

Stop! It’s not worth it! / My faith has strong armor / In my sturdy breast,

And bullets able to shatter / My faith / Do not exist,

Do not exist!

Nikola Georgiev defines this rough poetic style as one in search of expression, virtually hovering around various wordings of the meaning, and the message. He points to the splendid eclectics of Vaptsarov’s vocabulary brewing with quite incompatible chunks of speech: from biblical quotes and folklorisms to poetic and newspaper cliches. The analyst points to a special quality of Vaptsarov’s work displaying a tense relationship between the notions of Me and We, My and Our. All this makes it many-voiced, full of dialogue and argument. Nikola Vaptsarov was preoccupied with social themes, with the plight of workers, but quite remarkably his poetry raises in a most spectacular way the theme about the plight of art, like Hollywood movies, and poetry failing to respond to the real problems and aspirations of readers and viewers. He had an open, globally wide point of view and the geography of his Engine Songs runs from China to Moscow, from the Danube to Famagusta and from Ohrid to Spain. A great regional patriot of Pirin Macedonia, Nikola Vaptsarov was an outstanding example of a poet conveying universally humanistic messages. Even more importantly, his works are among the best anti-military works of that time across Europe.

The conspiracy and the firing squad

Like Hristo Botev in the late 19 c., Nikola Vaptsarov could not imagine a life of a professional poet confined to a quiet world of words and images. He believed that one should actively struggle for one’s ideas. And though not a member of the then outlawed communist party in Bulgaria, he was a convinced anti-fascist and in 1940 joined a communist conspiracy. In the course of several months he supplied communists with weapons, ID papers and accommodation. In March 1942 he was arrested and sentenced to death by virtue of the Law for the Protection of the State for organization of subversion against the German troops. Nikola Vaptsarov was shot by the firing squad on 23 July 1942.

Shortly before his death, in prison, he wrote the following:

The fight is hard and pitiless.

The fight is epic, as they say.

I fell. Another takes my place –

Why single out a name?

After the firing squad – the worms.

Thus does the simple logic go.

But in the storm we’ll be with you,

My people, for we loved you so.

A posthumous celebrity

Once the communist regime took over in Bulgaria in the 1940s, Nikola Vaptsarov – his persona and poetic work – were made into a banner by the communist party though he had never been its member. His poetry featured extensively in school textbooks. In 1953 the poet was posthumously given the International Peace Prize of the World Congress of Peace. The distinction was received by his mother, Elena Vaptsarova.

Nikola Vaptsarov’s status of posthumous celebrity came under threat in the 1990s, after the collapse of the communist regime in this country. Some democrats and educationists called for expelling his work from textbooks. Fortunately, this outrage did never take place.

We wind up this installment of Intense Literature with a few words of poet and literary critic Marin Bodakov:

“I can recall the words of Elena Vaptsarova after the death of Nikola Vaptsarov, words that can be interpreted ideologically and with communist rhetoric. I however think that we ought to read them as the words of a dignified mother and a strikingly intelligent woman. To quote Elena Vaptsarova: ’The dear one, he became the bridge for others’. And so we have seen lots of noisy groups passing over that bridge; but we have also seen many humble people passing over it with a troubled drive not in the feet, but in their hearts; ones deprived of daring and bread, to quote Vaptsarov if I may. And he was intelligent enough, hardworking and charismatic to achieve everything in his life: to be a brilliant naval officer, to be a popular writer, very popular indeed. In spite of all this Nikola Vaptsarov chose to be a worker in times of great trouble, to be able to express his solidarity with the masses that were socially excluded. And that this choice was a fully conscious, not to say a suicidal decision, shows in a note written by his wife Boika that goes as follows: ‘There was strong conviction in him instead of a dash’. This conviction is key, because Nikola Vaptsarov was very much troubled by what he termed ‘false chimeras’.”

Verse translated by Peter Tempest

The first EU Songbook has been released, featuring six songs from each of the 27 EU member countries and Ode to Joy, the anthem of the European Union, reports BTA. The Songbook, a non-profit Danish initiative, has no financial ties to the EU,..

Days of Bulgarian culture will be organized in Madrid between November 9 and December 31, 2024, BTA reported, citing Latinka Hinkova, president of the Association of Bulgarians and Artists "TREBOL" and head of two Bulgarian Sunday schools in Torrejon de..

The national awakeners of Bulgaria are the individuals for whom we feel not only gratitude and admiration, but also perceive as some of the most significant figures in our history, because they awaken our sense of national togetherness. However, what is..

A photographic exhibition "Sylvie Vartan and her Bulgaria", dedicated to the French music icon of Bulgarian origin, will be open to the public from..

+359 2 9336 661