The majority of Bulgarian Jews are poor craftsmen or ordinary workers. Growing up among Greeks, Armenians, Turks and Gypsies, the ordinary Bulgarians cannot understand the struggle against the Jews. The racial issue is alien to them.” This is how the German Minister Plenipotentiary in Sofia during the Second World War, Adolf Heinz Beckerle, described Bulgarian national psychology. Probably this is the key to unravelling the phenomenon of the "Saving of the Bulgarian Jews".

First of all, this was an act of unprecedented scale - Bulgaria saved over 48 thousand people. Another nation that saved its Jews during fascism, the Danish nation, sent nearly 8,000 of them to Sweden, and in Albania, in the mountains, about 2,000 Jews were hidden in the mountains. The other peculiarity of the Bulgarian phenomenon is that salvation took place in Bulgaria’s own territory. That is why at the end of the war the number of Jews in Bulgaria was greater than at the beginning.

The events

On March 10, 1943, Metropolitan Kiril of Plovdiv and Exarch Stefan of Sofia prevented the deportation to the Nazi concentration camps of hundreds of Jews from Plovdiv. Seven days later, then-Deputy Speaker of the Bulgarian Parliament, Dimitar Peshev, wrote a letter against the deportation of Bulgarian Jews, supported by 42 deputies. Thus, with the intervention of politicians, clergy and the public, Bulgarian Jews were saved.

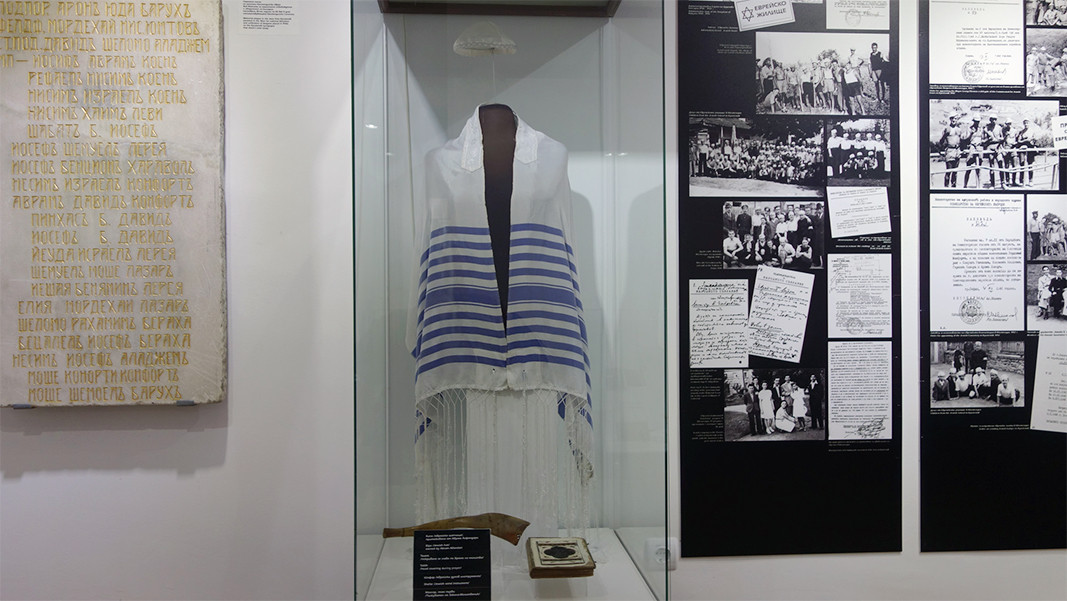

A permanent exhibition in the Dimitar Peshev House-Museum in the town of Kyustendil tells through authentic personal belongings, photos and facsimiles about the events of March 1943. Today's Bulgarian historians, politicians and public figures define the efforts to save the Jews in Bulgaria during the Second World War as one of the greatest moments in the Bulgarian history of the 20th century.

If you save one person, you save an entire universe, an old Jewish saying goes. Amalia Aronova is one of the rescued Bulgarian Jews. She lived in Sofia, and in 1951 moved to Israel, where she worked as a laboratory assistant in a hospital.

In front of the correspondents of the Bulgarian National Radio in Israel Fenya and Iskra Dekalo, Amalia talks about the years when her family was displaced from Sofia and sent to the Burgas village of Kamenovo. She recalls that the villagers turned their backs on the strict rules against the Jewish people displaced from the Bulgarian capital and accepted the Sofia Jews more as the family of a seconded specialist than as people in forced isolation. At that time, internees were not allowed to live in Bulgarian houses, were forbidden to go to shopping for more than 2 hours, and even children had to wear a yellow badge.

"We lived in a rented house, just like other people. They brought us bread and various gifts. People did not make any difference between a Jew and a Bulgarian,” says the woman, who today lives thousands of kilometres away from Bulgaria:

"I want to tell you a very interesting case. This was after September 9, 1944. The regime changed and the village had a new mayor. The mayor of the village arrived at home with an official. He carried a long knife. He asked about Dad: "Where is the doctor?" Mom said, "He's resting," and the mayor said, "If it’s possible, let him get up and put on his jacket." There was a yellow badge on his jacket. Mom went to tell my father and he put on his jacket. Then the mayor approached my father. He cut off the badge with the knife. He threw it and said: "Now you are equal citizens of Bulgaria."

Continuing the journey in her memories, Amalia Aronova shares that her classmates also treated her very well.

"I was going around the village without a badge. Before we were displaced, we lived in Sofia. Armenians lived on the ground floor, Jews (i.e. us) on the first floor and Bulgarians above us. When we went to this village of Kamenovo, we had to give the things we had at home to the Armenians and the Bulgarians. And, of course, we did not expect to return. When we returned in the fall of 1944, everything was returned to us. They said, "These are your things and they belong to you." I still remember their names. The Armenians were called Simpadovi. They had a factory for stoves, and the Bulgarians were Georgievi. They were from the family of a senior official at the National Bank. "

There are hundreds of stories of compassion, humanity and support, told by the saved Bulgarian Jews and their heirs over the years. And their connection with Bulgaria remains alive to this day, because it is part of their life universe.

For Radio Bulgaria from Tel Aviv - Fenya and Iskra Dekalo

Photos: archive and digital-culture.euIt is exactly 100 years on 1 June, 2025 since the date was proclaimed International Children’s Day. And, as is the tradition, it is going to be a colourful day with lots of different events for the children throughout Bulgaria, with Sofia being the..

As every year, on the last Saturday of May, the town of Karlovo plays host to the Rose Festival, dedicated to the beauty and fragrance of the roses of Karlovo, and to spring. The tradition goes back to the turn of the 20 th century. The..

More than 2,200 children from all over Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Moldova, the Republic of North Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Ukraine are taking part in the 22 nd International Children's Ethno-Festival "The Children of the Balkans..

As we approach the height of summer and temperatures soar, access to water becomes essential. We remember the hardships of summer 2024, when hundreds of..

A retaining wall alongside the Banshtitsa River in Kyustendil is being transformed into the country’s longest legal graffiti art wall, according to a..

On June 21 and 22, the Expo Center "Flora" in the Sea Garden in Burgas will turn into a culinary arena , where the best paella masters from all over..

+359 2 9336 661